What’s to blame for too little water in Flathead Lake: climate or mismanagement?

Accusations of mismanagement have been flying, while dam operators point to the role of a rapid runoff of a modest snowpack.

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

3 of 3 free articles.

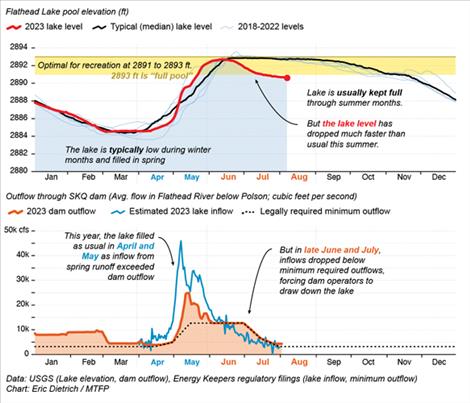

RONAN — The amount of water flowing into Flathead Lake peaked both lower and earlier than normal this year, frustrating those accustomed to the lake’s reliably clean, clear water for recreation, irrigation and power generation through the summer.

The dam-managed lake at the headwaters of the Columbia River system is currently 2.5 feet below “full pool,” considered the ideal level for using the lake’s numerous docks and ramps. The fallout from the low lake level has inspired political pressure and energized a series of well-attended “Save Flathead Lake” meetings where organizers have suggested dam mismanagement, not water supply, is to blame for unusable docks and slackening economic activity.

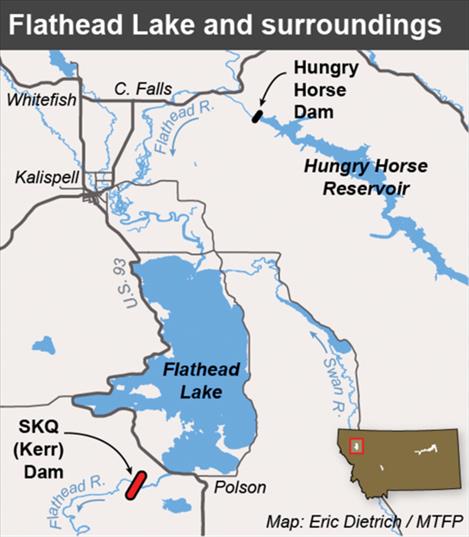

Operators of the Séliš Ksanka QÍispé Dam (formerly the Kerr Dam) counter that they’ve made the most of a modest snowpack that melted during a particularly warm stretch in May. There just isn’t any additional water in the system to fully refill Flathead, according to Brian Lipscomb, CEO of Energy Keepers, Inc., which manages the 85-year-old dam at the lower end of the lake for the benefit of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. Lipscomb said record low inflows, paired with conditions included in Energy Keepers’ federally administered hydroelectric license, are driving the lake’s depletion, which will continue into the fall.

During a conversation in early August with Montana Free Press, Lipscomb referenced data from the NorthWest River Forecast Center demonstrating how little water flowed into the lake from the various rivers that feed into it. Since October, the start of the water year, the inflow has fallen short of the 30-year average every month except May, an exceptionally warm month.

The high temperature on May 1 in Kalispell hit 86 degrees, breaking the previous record for that date by 6 degrees and exceeding the average high by 26 degrees. Water from the Flathead’s primary feeder stream, the Flathead River, came careening into the lake, surpassing 35,000 cubic feet per second when it peaked on May 5. The peak came a full month earlier than normal at that particular gauge, which has 70 years of records. By June 1, flows dropped to less than half their usual level.

Further complicating the issue, there was virtually no snowpack remaining in the Flathead watershed by June 1 to sustain summer streamflows and lake levels. A June water supply outlook prepared by the Natural Resources Conservation Service noted the record early melt-out that had occurred, or was anticipated, at four northwest Montana snowpack monitoring stations. That includes the Flattop Mountain station located 6,300 above sea level. It lost all of its snow by June 6 — three weeks earlier than normal. All forks of the Flathead River were forecasted to drop below 60% of their average streamflows for June and July, per the agency’s report.

Lipscomb said when he sees trends like that — an early, snowpack-decimating warm spell accelerating runoff — it suggests that he’ll have a short window to capture water to fill Flathead Lake followed by a difficult stretch of weeks when the lake will drop to ensure the Flathead River below the dam continues receiving water. It means, he said, that the 26-mile-long lake won’t stay at full pool to sustain some recreational uses — more specifically, an elevation of 2,891 feet to 2,893 feet — through the summer.

Energy Keepers’ monthly filings with the Interior Department — another license requirement — illuminate how abruptly that dynamic developed this year.

“May natural flows into Flathead Lake were 106% of average,” according to the June 1 filing. “Through June we will refill [near 2,893 feet] for summer recreation.”

By July 3, the forecast was grimmer. “June natural flows into Flathead Lake were 40% of average, a 56% decrease from the streamflow forecast in early May,” the report reads. “Due to the low inflows into the lake, it is expected the elevation will continue to decrease to meet [fishery-related] minimum flow objectives and summer recreational preferences will be impossible to meet.”

Lipscomb said it isn’t just dock owners reeling from the low water supply. The lake drawdown puts his company in a tight spot, too, since restricting outflows to the absolute minimum means there’s less water spinning electricity-generating turbines. Energy Keepers, Inc., which provides considerable funding to the CSKT government by generating, selling and trading power, is currently sitting at record low electricity generation, he said. His company has operated the dam since 2015 when CSKT became the first tribe in the U.S. to retain full ownership and operation of a hydroelectric project, the culmination of a 30-year effort. The dam is located on CSKT land; the northern boundary of the Flathead Reservation dissects the lake.

Lipscomb heard comments earlier this summer by Gov. Greg Gianforte and other elected officials suggesting that Hungry Horse Reservoir, which sits above a federally managed dam on the South Fork of the Flathead, should be tapped for more water. He said such calls are misguided. “There’s just not water there to move,” he said.

Creating an appreciable difference in Flathead Lake levels would require a dramatic decrease in the Hungry Horse’s water levels, which are already low, Lipscomb said. Hungry Horse’s operators would be asked to violate requirements established more than 20 years ago geared toward protecting the Columbia Basin’s fisheries, including Hungry Horse’s own population of bull trout, which is listed as a threatened species.

“There’s nobody to blame, no one entity to blame,” Lipscomb said. “It’s the conditions that we have, and we have changed conditions.”

‘Caught In The Grip Of Global Warming’

Retired ecology professor and former Flathead Lake Biological Station director Jack Stanford said he can understand why this year has come as such a shock to people, particularly those who may have recently purchased property on the lake as part of a larger pandemic-relocation trend, but he warned that years like this will become increasingly common.

“Someone who comes here and buys a house last year and has a vision of [the lake] from last year and suddenly the water is 24 inches down — I can see why people say, ‘What the hell is going on here?’” he said.

Stanford said he’s happy to explain the dynamics at play on Flathead, having studied them both here and on other Montana rivers. Warming temperatures wrought by climate change are eating into snowpacks earlier and earlier, decreasing the snow available to sustain stream flows through the summer. In June, Stanford testified about this trend as an expert witness in the Held v. Montana youth climate trial.

“Nearly all the rivers in the state — including the Flathead — have declined in total flow because of reduced snowpack,” he said in a conversation with Montana Free Press. “The runoff has moved earlier in the year, and it has also happened very fast. One warm, or even hot, spring and that snowpack goes. The next thing you know, it’s July 1, and the flows in the river are minimal.”

Asked what policy shifts that knowledge should inspire, Stanford had a ready answer: “What has to happen is people start realizing we’re caught in this grip of global warming that’s got us already reeling, and it’s just going to get worse unless we start changing the way we’re living,” he said. “We might have a big runoff next year and people might say I’m full of crap, but in the long term, the modeling and assessments suggest that water supply is going to decrease dramatically.”

Stanford also said property owners and land managers would be wise to invest in floating, rather than fixed, docks to adapt to increasingly variable lake levels.

“There’s a lot of them around the lake,” he said. “There’s one at Yellow Bay; it works just fine.”

For Kate Sheridan, executive director of Flathead Lakers, a nonprofit organization that advocates for a healthy Flathead watershed, there’s a silver lining to the lake’s diminished state. It has underscored, she said, how enmeshed Flathead is in the larger Columbia River Basin and how integral it is to a whole host of uses, ranging from power generation and crop irrigation to recreational pursuits.

“I think we’re realizing that we aren’t the only ones on the Columbia River system,” she said. “I think people are starting to put the pieces together and be reminded that we are part of this bigger picture.”

‘Save Flathead Lake’

About a dozen miles south of the Flathead Lakers office in Polson, those attending the first in a series of “Save Flathead Lake” meetings were offered a different explanation for the low lake levels, one involving the alleged unlawful seizure of water rights, the CSKT Water Compact and incompetence or greed on the part of Energy Keepers, Inc.

After Lake County Pachyderm Club President Micah Robertson offered a prayer for relief from “these harmful things that are happening in our community” and for the safety of the firefighters battling regional wildfires, event organizer Linda Sauer told the 100 or so people in attendance that she hoped they’d leave feeling “energized and motivated to fight to save our beautiful lake.” Then she laid out her case.

Isn’t it interesting, she suggested, that managers of the SKQ Dam and Hungry Horse Dam navigated previous droughts without such a marked decline in summertime lake levels when the former was jointly operated by CSKT and NorthWestern Energy? Sauer pulled U.S. Geological Station data from both the Flathead Lake and the Flathead River gauge below the dam to make her point, arguing that outflow through the dam had increased in May during a “critical moment” when the operators should have held more back to reach full pool.

“That early release prevented Flathead Lake from ever reaching full pool, and the level descent began in mid-June instead of, normally, that would have been July 1,” she said.

In response to that assertion, Lipscomb, with Energy Keepers, Inc, told MTFP that the lake came within a couple of inches of full pool on June 13 and filling it any higher at that time would have put his organization in jeopardy of overfilling the lake in the event of an unexpected inflow spike — something its license forbids. He also argued that, given the discrepancy between inflow and license-mandated outflow that started in June, the drawdown was unavoidable.

Sauer also incorporated the CSKT Tribal Council’s intention to purchase non-tribally owned land inside the Flathead Reservation boundary in her presentation and noted that in 2014, then-vice chair of the council, Carole Lankford, equated assuming operation of the SKQ Dam with “asserting management and control over the Flathead Lake and Flathead River.”

“Did we accept that at face value and say, ‘What does that mean to me?’” Sauer asked. “I don’t think so. I think we weren’t paying attention. So here we are today.”

Sauer urged those assembled to record their damages from low lake levels, share them on a recently launched website established for that purpose and record videos of their plight. She encouraged any business owners in attendance to describe their experiences for a videographer who’d set up in the community center for the event.

“How many of you have seen the empty marinas? You know those restaurants that have those boat slips where you can ride up in your boat and have a lovely dinner at this nice restaurant? They’re suffering. The boat rental places are suffering,” she said. “The impact on business is tremendous.”

In addition to garnering material for a potential lawsuit, Sauer said efforts are underway to introduce legislation in U.S. Congress to remedy the issue before next spring’s runoff.

“We have to believe our eyes, believe what we know,” Sauer continued. “Drought is nothing new … Early runoff is not new. So climate change isn’t a good explanation. I won’t call it an excuse. I’ll call it an offered explanation. It’s not a good one.”

‘Extremes Within Those Extremes’

It’s not lost on Lipscomb that Flathead Lake reached, and in fact exceeded, its full pool last year. He said it’s part of this larger climate change-related trend where there are “extremes within those extremes.”

“The worst,” he continued, “is the swings.” He said oscillations should be front-of-mind for those working in the water and energy arenas. Not only is the Northwest especially dependent on hydroelectric power, but it’s also seeing spikes in grid-straining power demands related to heating and air-conditioning use during cold snaps and heat waves, Lipscomb said.

Asked about specific policy measures to address the increasing unpredictability of the Columbia River system and the dozens of dams located along it, Lipscomb demurred.

“I’m not a politician, I’m not a policymaker,” he said. “It would be disastrous if I did not manage this facility pursuant to what’s going on. So we will.”