Cherry growers work year-round to ensure safe practices, pest-free fruit

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

3 of 3 free articles.

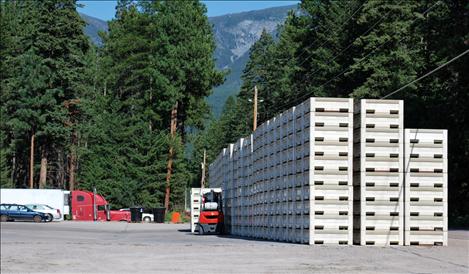

As the cherry harvest ends, the shipping process and marketing runs smoothly largely to the program’s safety and legal requirements that are part of the harvest itself.

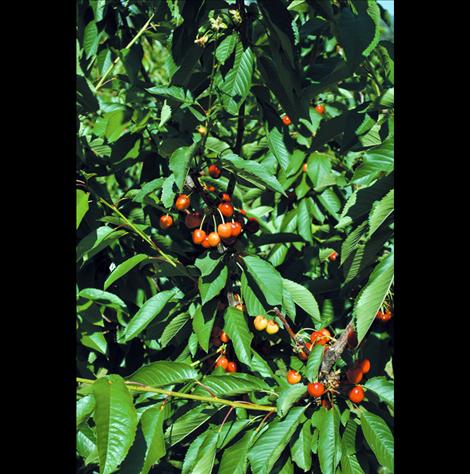

Included in this process is the use of commercial sprays to protect the cherries from bugs, such as the Mediterranean Fruit Fly and the Girasol Folia Spotted Wing Fly. The latter was introduced to the United States in 2008 through cranberries and wild berries that were imported from California.

Barbara Kaye, who has Gateway Orchard on Highway 35, explained that the fly only has one life cycle and that bait spray attracts the fly, then it gorges on it and dies.

Another problem for cherries is powdery mildew, which Kaye said is in the area now.

Fighting pests means purchasing chemicals. Chemical prices have gone up and certain ones that are now banned were less expensive, she said.

“It’s costing us three to four times more than it used to, to produce the product,” Kaye said. “So many of the sprays have been outlawed (so) its a challenge growing cherries. It’s no picnic. My spray bill runs me about $3,300; I’ve never paid that much money. In the ‘80s and ‘90s we were selling cherries for 50 cents per pound. You can’t do that when you’re putting out thousands of dollars to put out a crop.”

Already, she’s done four sprays with different chemicals. However, she says, once a problem is in the area, that is really all you can do.

Depending on what growers need, commercial sprayers can come out in rotations so the crop doesn’t build up a resistance to the chemical itself.

“We have to do a lot of pesticides (as a Co-op) because we can’t ship them interstate. We can’t even send them to Washington or California if they don’t have certain sprays that are now required,” Dick Beighle, a member on the Flathead Cherry Growers Co-Op board said. Beighle also has an orchard on Finley Point.

There is a dormant spray used for mold and fungus, and that one is done at the start of the season. After that they spray for nutrients, which include nitrogen and calcium. The last stages of spraying are the pesticides because of the fruit flies and other bugs.

“It’s really a problem around here, a problem for everyone,” Beighle said about the fruit fly. “They live out in the forest and burrow into the cherry and lay eggs, and the larva falls into the ground.”

Some growers, including Kaye, make traps for the Mediterranean bug that’s basically a plastic container that holds an inch of apple cider vinegar.

The natural vinegar solution is one of several naturally occurring products organic growers can utilize instead of chemicals, but without sprays, organic growers can only offer their cherries locally.

“Some use soap and stuff like that, things that are non-toxic,” Beighle said. “Organic growers can’t ship out-of-state without sprays; they have to find a local market.”

It’s not cost effective for organic growers to try and make a profit by marketing through Monson Fruit Company, according to Brian Campbell, field representative for Monson.

“It’s so specific for organic cherries,” Campbell said. “You need separate bins and trucks. The cherries have to be packed on a separate line and can’t intermingle with (non-organic) cherries at all.”

Campbell said that theoretically it could be done here, but “the freight would kill ‘ya. Unless you had 20 acres we can’t make it work.”

Growing organic has additional costs as well.

Organic cherry orchards cannot use treated lumber fencing, and good organic sprays are two to three times more expensive.

“Some people end up spraying as much or more,” Campbell said.

From the beginning of cherry season, multiple sprays in non-organic orchards are applied to cherries due to regulations, according to Beighle.

The Flathead Lake Cherry Growers Co-op is now implementing Good Agricultural Practice, also known as GAP certification.

“Last year a bunch of us got certified, but this year, it’s mandatory,” Beighle said.

Last year 28 growers became certified; this year, 50 growers were involved and 10 percent got audited.

“Becoming GAP certified is going to become a natural thing for most produce and vegetables and fruit to be certified,” Beighle said.

“People want that, because every year you read some fruit or vegetable was polluted, so it makes sense to do it and it makes you more aware of what you should be doing.”

GAP involves a heavy certification process and a detailed regulations book with guidelines that all orchards must enforce. The qualification guidelines are in a large book that every Co-op member has to follow quite carefully. Regulations involve irrigation and agricultural practices that enable them to become GAP certified globally.

“Your fruit will ship anywhere that’s qualified, and big buyers are demanding now that all fruit they buy has to come from orchards that are certified,” said Ken Edgington, Media Director for the Co-op board.

Last year, Walmart and Costco were the first to switch to purchasing only GAP certified cherries, according to Beighle. Now there are 32 food chains that want the GAP system.

“If you’re not gap certified, you can’t bring cherries in,” he said.

The certification process itself is a massive document record keeping process that involves every aspect of growing fruit.

Co-op growers are randomly audited to ensure quality.

“They have the ability to shut you down if you aren’t qualified,” Beighle said.

A short time window is allowed for an orchard grower to correct a problem, but if it is something that doesn’t get corrected, the whole Co-op gets shut down, according to Edgington.

“There’s a lot of pressure to get it done. ... Monson won’t take any non-certified cherries.”

Bruce Johnson, President of Flathead Lake Cherry Co-op, said that as a collective whole, the Co-op encourages the GAP program and that most produce growers are doing more to increase worker safety and better food safety.

“As an agricultural crop, just like anything from corn to beans, we all fertilize. We are also pretty careful about the Environmental Protection Agency,” Johnson said. “My orchard does not adjoin the lake or stream; we’re 2,000 feet from the lake.”

Irrigation system requirements are included in the GAP certification process, as are rules that apply to migrant workers, including ID verification and safety.

Johnson explained that there are 18 different kinds of ID verification a migrant worker can show, but one valid form is all that is required from workers so the grower can avoid facing a hefty fine.

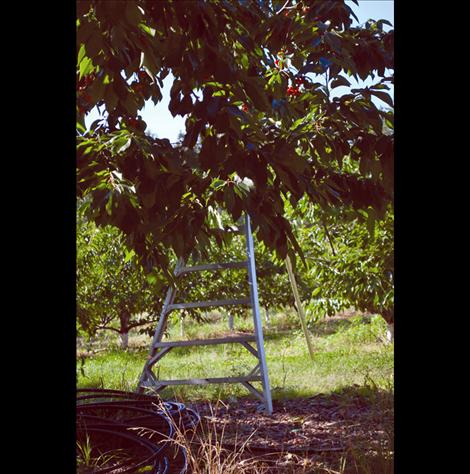

To ensure safety, pickers cannot put their hands on a ladder if it has been stepped on and there must be someone who is first aid and CPR certified on the grounds.

The guidelines are not just a means to produce good fruit, but also a way to recordkeep the trail of a product from packaging to the store that purchases it.

“If something happens they can look at store records and that person and packager will trace back to the section of orchard where that piece of fruit might have been grown,” said Edgington. “It’s good for the consumer because it may not be the grower that contaminated fruit.”