Addiction recovery home opens in Polson

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

2 of 3 free articles.

POLSON – Jay Brewer stood outside the new drug and alcohol addiction-recovery house – one of the first of its kind in Montana – on a warm spring afternoon with a smile on his face.

“Everything is surreal right now,” Brewer said as he looked at the ordinary white house being used to help combat addiction and homelessness in Lake County. “It’s amazing to have this place.”

The house isn’t hard to find in Polson, but the location isn’t being published to help the residents.

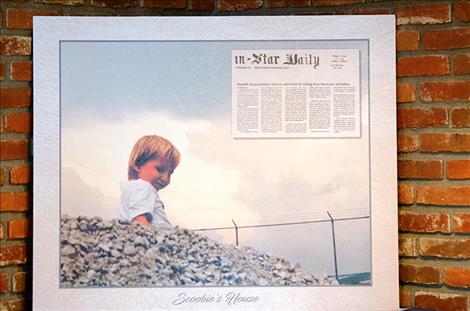

The two-story structure is a place men can call home for about a year to learn skills to help them recover. Brewer is the Lake County Drug Court Coordinator and a member of the Never Alone Recovery Support Services board. He is also one of the people who helped develop the residential recovery house with Never Alone. He named the program Scoobie’s House. When he starts to explain the origin of the name, the tears come from a place of grief.

“Every day, I have to ask for forgiveness,” he said as he starts to tell the story about his three-year-old son Stephen who died on March 5, 1992. Stephen was diagnosed with leukemia shortly after his first birthday. The family was living in Illinois. His nickname was Scoobie.

Doctors said there was nothing more that they could do for the child and sent him home to die. Brewer had a history of drug addiction and having a constant flow of morphine in his home for the child was an issue. A newspaper article Brewer displayed at the open house said Brewer was denied services for his son due to his past history and nurses feared going into the home.

The article continued to say that another nurse vouched for Brewer. “Jay has been there all the way for Scoobie and has done well with his care.” But it wasn’t enough. Brewer said lawyers and police escorts were involved as he fought to allow his son to stay at home. The child was taken back to the hospital where he died. “My biggest regret is not being able to bring my son home to die because of my addictions,” he said.

Brewer went on to become an addiction counselor and moved to Montana where he focuses on his family and recovery. He said working his recovery program, asking for help when he needs it, and helping others keeps him going. Developing the recovery house is the way he honors his son. He said recovery is a life-long process. “Addiction never goes away. It’s something you have to keep working at. Once an addict, always an addict. And dope is everywhere. The change has to be in you.”

When he talks about developing the recovery house, Brewer said he can’t take all of the credit. He said many people have helped work on the project with contributions coming in the form of funding and treatment support. He said the new house managers, Willow Coefield and Merlynn Becker, help keep things going. “I have to give credit to Don Roberts,” he said. “He is one motivated man, committed to his community.”

Roberts runs Never Alone Recovery Support Services providing long-term recovery management for individuals to overcome addiction. He is a licensed addiction counselor and is also working on a recovery program like many of the people working with NARSS. The Scoobie’s House is part of the NARSS program.

“It’s amazing how far we’ve come in a short time,” Roberts said. “We started with nothing.” He said the NARSS program in Ronan is moving to 112 Main Street. He thanked the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes for providing the building.

Roberts said that a narcotics anonymous program was created in the county in 2015. The Lake County Drug Court started in 2017. After drug court was developed, it became evident that support services were needed so NARSS was started. “Now, we’ve got the residential services,” Roberts said. “Our end game is to eventually build a larger facility.” NARSS also plans to develop a residential program for women.

Addiction recovery depends a lot on community, he said. “The biggest thing we do is community,” Roberts said. “And it’s important for addicts to have a place in the community and community support. We need to involve the community in a culture of recovery.”

Scoobie’s House was modeled after another program in Kentucky, designed to reduce the state’s drug and homelessness problem with peer support, living skills, job responsibilities and by establishing new behaviors. The United States Department of Health and Human Services said that this is a model that works.

Scoobie’s House already has four residents. In February, the first resident moved in. To become a resident, men need to complete an application and can stay for about a year or so, depending on the individual. The program utilizes peer support so residents are allowed to participate in the selection process for new residents.

Nakota, 32, is one of the first residents. He said he started using drugs as a teenager and eventually ended up in jail. He said the treatment programs he attended in the past didn’t work for him, but he was having better results with the peer support model. He said he needed the program to work so he could take care of his children. “My kids motivate me,” he said. “I have one more on the way, so I need to figure this out. It’s time to do something different.”

The recovery house has a structured environment where Nakota and other residents can learn new living skills. They make food together, shop together and eat together. “Recovery comes first, then a job, and then they work on getting their own place,” Roberts said.

Nakota gets up at 8 a.m. and has a cup of coffee then he goes to treatment meetings. He comes home in the afternoon and has lunch and works on his 12-step recovery program. After he gets his recovery program established, he plans on looking for a job.

Support is one of the key elements of recovery at the house. Brewer said the recovery community acts like “a bunch of bookends.” He explained that several people including staff, therapist and other residents support the person in recovery. “We have people from Dayton to Arlee willing to support each other. I think that this model of support works.”

District Court Judge James Manley was at the open house to celebrate the program’s success. He said the recovery house was desperately needed. “People come out of drug court and end up couch surfing and in the same environment they were in before and that doesn’t work. They need a place to recover. Jay and Don saw a need for this in the community and made it happen. This is remarkable.”

He said the Lake County Drug Court supports the recovery house but it’s not part of the court system. “It’s not really ours,” Manley said. “The state wouldn’t let the court have a recovery home because of liability issues. We had the funding but couldn’t do it. This nonprofit was formed so that it could be done.”

Manley believes treatment is a better way to help people with addiction. “You can’t lock people up and incarcerate the addiction out of them. It doesn’t work. The need for treatment is unbelievable. I did my own unscientific study and found that of 500 felony cases in my court, 92 percent were addicts. Many have undiagnosed mental illness, and many have children. Our inability to address this epidemic is impacting the next generations.”

Funding for the project came from the Virginia Lebkisher Memorial Foundation, who was from Washington. This year’s donation from the foundaiton was for $52,000 with additional funding set for the future. Lebkisher left her nephew Doug Hammill of St. Ignatius in charge of distributing her trust. Hammill read a newspaper article about NARSS and thought the program would be the perfect fit for his aunt’s vision. “I asked her in her last years how I should find the people in need,” Hammill said. “She said I should find the people down under the bridge who need help. She was saying that she wanted me to help one person at a time in a way that would really help them.”

Lebkisher’s brother suffered from mental illness and addiction. “Her motivation was his life and torment. She wanted to help people suffering like he did,” Hammill said of his aunt. He looked around the living room at the recovery home. He saw the couches, the piano, the kitchen and stairs to the bedrooms. “This feels like her dream,” he said. “This feels like it’s working.”