A family grapples with the ripple effects of son’s mental illness

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

3 of 3 free articles.

By Briana Wipf Cut Bank Pioneer Press

Bobbing his head to the music, swinging his brown jaw-length hair from side to side, Jack Pierre sings dramatically along with the music, the Killers’ “Somebody Told Me,” sometimes letting the strident vocals of lead singer Brandon Flowers take over, other times belting out the music in his own clear tenor.

Jack recorded it about a year before he died by suicide in August 2016.

This Jack, caught in a video goofing around, enjoying music, “his outlet,” is the Jack his family and some friends knew. But Jack, who dealt with mental illness and suicidal thoughts from a young age, also struggled to relate to his peers and gained a reputation as being a scary kid, his mother, Jennifer Van Heel, says.

Van Heel tried for years to get Jack appropriate help, which at various times included medication, counseling, and inpatient treatment, but nothing seemed to improve his quality of life in a substantial way.

Ultimately, he was a lonely kid. Counselors would tell him that he needed to love himself. Jack insisted that he loved himself just fine; it was other people who seemed to go out of their way to remind him that he was different.

“What Jack hated was he did not fit into what society thought he should be, and nobody would accept him for what he was or allow him to just be,” Van Heel says. “Not only do people not accept you, they have to let you know.”

Rachael Skiera, a friend and classmate of Jack’s, says that while she knew Jack was bullied in school, she did not see him publicly show a negative reaction to the bullying.

“Looking back on it, he was probably just trying to protect himself from getting hurt,” Skiera says.

In 2016, when Jack ended his life, Montana led the nation in its suicide rate, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nationally, suicide regularly ranks within the top ten leading causes of death, according to the CDC. The 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey of Montana’s adolescents, compiled by the Montana Office of Public Instruction, found that 20.8 percent of students reported having seriously considered suicide in the past year, while 9.5 percent of students reported having attempted suicide at least once in the last year.

But suicide in Montana affects all age groups. The 2016 Suicide Mortality Review Team Report, published by Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, indicates that more than half of all suicides in Montana between 2014 and 2016 occurred in people between the ages of 35 and 64. Yet suicide is a leading cause of death for young people, the report states. The majority of people who killed themselves had mental health issues and many had exhibited warning signs, according to the report.

Rural communities face unique challenges with respect to mental health care. According to Brooke Dager, a psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner at Marias Healthcare in Shelby, rural areas lack resources that make mental illness “difficult to address and treat.”

A lack of inpatient beds for people in crisis is one concern, Dager says. Great Falls is the closest inpatient facility for adults. Children must go either to Helena or Billings for inpatient care. Dager wishes there were more inpatient beds, but treating people before they need crisis care is important too.

“Really it’s just preventive care,” she said, “more people being educated about warning signs.”

To that end, Dager says the local community has worked hard to provide mental health first aid training to parents and educators and to raise awareness about adverse childhood experiences, such as physical or emotional abuse, which may affect a child as they grow into an adult.

Van Heel has seen the community change in that regard, too. But she worries that change has yet to take root in a significant way that can change the attitude toward people with mental illness.

That stigma is “probably one of the major barriers” to getting treatment, Dager says. “They don’t want to be labeled mentally ill.”

Contemplating suicide does not necessarily mean one has a mental illness, she adds. Many people at some point or another in their lives go through times where they think about ending their lives.

From a young age, Jack displayed character traits that set him apart.

“When he was 5, he wanted to move to the rainforest to save all the snakes. And it always disappointed him how little everyone cared about how the snakes and everyone else were impacted,” Van Heel says.

Jack would continue this way, showing concerns for big-picture problems that many of his friends had difficulty relating to.

“He was always way more worried about huge things and wanted to try to fix everything,” she adds.

As he grew older, he read voraciously. He checked out books from the library that had not left the shelves for decades, exploring with Leo Tolstoy and Salman Rushdie. He became interested in world religions.

“Jack was looking for answers and why he was the way he was and why he didn’t fit into society,” Van Heel says.

When his exhaustive study of religions did not satisfy him, he turned to science and became interested in quantum physics. He loved to tell his mom about what he had learned.

People who knew Jack learned not to argue with him on subjects he had studied because he had his facts on hand.

“He was smart and against the grain a lot of times,” Van Heel says.

Skiera remembers Jack being smart and applying that intelligence through his sense of humor. She moved to Shelby as a fourth grader and, because their last names fell near each other in the alphabet, often found herself near Jack in the seating order in class. They became friends.

“He was very intelligent, very witty, quick to make jokes, but never taunting or mean about it,” Skiera recalls.

Jack loved children, especially babies. Children under 5 were not cynical and were not judgmental, he said. He was especially fond of his niece, Annie, who was almost a year when he died. He sang to her constantly. “Seven Nation Army” by the White Stripes was one of their favorite songs.

Skiera remembers Jack’s love for his niece. When she was born, “everyone saw a total change in him. He was completely obsessed with taking care of his niece.”

He loved animals, especially snakes, and had several. His last was a ball python named Ash. He could relate to snakes, he would say, because they, like him, knew what it was like to be feared and not understand why.

He was a talented artist and writer. He loved to sing and loved music, “everything from Jack Johnson to heavy metal that made my ears bleed,” Van Heel says. He enjoyed the outdoors and liked to run.

He had sometimes contentious relationships with his siblings, but he shared a close bond with his older sister Shyanne and his younger sister, Melanie. He butted heads at times with his stepfather, Van Heel’s late husband, Casey, perhaps because they were so much alike, Van Heel says. Jack’s relationship with his father, Jason Pierre, was strained at times, but toward the end of his life, he and his dad were on better terms, and Jack even lived with him for short periods, once in Louisiana and once in Great Falls.

“It was hard to see him through the ‘a lot’ [of times] that wasn’t so good,” Van Heel recalls. “Living with someone who struggles with that is freaking hard.”

Van Heel admits her attempts to help Jack sometimes meant she spent less time with the rest of the family, and that took a toll too.

Jack’s family knew his struggles and loved him. Outside the family, some people were less forgiving. Some thought he was trouble, Van Heel says. For a while, he had dreadlocks. He painted his fingernails black and wore black eyeliner. Some peers, teachers and employers, were scared by his dark outward appearance.

But those who got to know him learned he was a polite young man who was well read and intelligent.

As he hit puberty, his mental health problems began to compound, and his struggles began to increase.

Always close to his mother, Jack confided in her that he was engaging in self harm.

“We talked about that a lot… I could relate because I did the same thing,” Van Heel says. “That was one of my downfalls, because I’m still here, I made it through, so I figured my kid would do the same.”

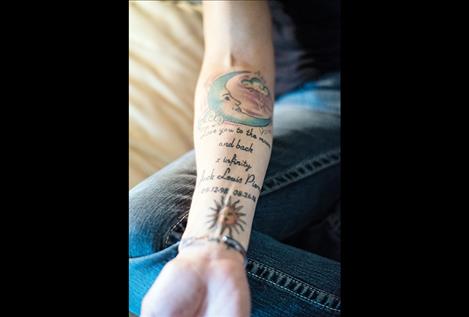

Eventually, Van Heel stopped cutting herself; instead “I graduated to tattoos because they’re prettier,” she says wryly.

For years, Jack also confided in his mother that he was miserable, that he wanted to die.

“He didn’t hate himself but enough of society hated him and let him know what a freak and how different he was and he didn’t fit,” she says.

He was a burden, he would say. Everyone would be better off without him. It would be easier for everyone if he were gone.

But he stuck around, Van Heel says, because he knew it would hurt people, especially her.

“I told him it would do more than hurt my feelings,” she says. “I would try to let him know that dying was not the answer… I tried to convince him that there is so much more beyond this and so much more for him.”

Sometimes, Jack believed her. Other times, she knows he did not.

Van Heel tried to get help for her son, in Shelby and outside of it.

“I can’t even tell you how many counselors we went through,” she says.

From age 7 to when he began puberty, Jack was on medications for ADHD. Those medications stopped being effective and “they kind of bounced him around” on different medications for depression and anxiety after he began puberty.

They tried counseling in tandem with medication. When the side effects from the medications were too much for Jack, they tried counseling only. He tried inpatient treatment. He spent time in a therapeutic group home in Billings, which was helpful. But Jack missed home.

He underwent a full psychiatric evaluation at a facility in Kalispell, where the staff helped get Jack on medications that were be more helpful for him. But still, Jack’s past mental health diagnoses seemed to follow him.

With those labels Jack – who already could be off-putting to people due to his dark clothes, dreadlocks and sometimes sharp tongue – was pushed even farther afield, according to Van Heel.

“People did not want to deal with him,” Van Heel says. “You tell people your kid has a mental illness, and everyone steps back 10 feet.”

The power of those labels – and people’s responses to them – have made Van Heel rethink her decisions about Jack’s treatment.

“If I could go back, and change my mind and not allow him to be further diagnosed and labeled, and have to do special ed(ucation) because of emotional distress, I would do it in a heartbeat,” she says. “Being labeled as a manic depressive and (having) anxiety with suicidal tendencies was a huge red flag that screwed things in a lot of ways.”

Now, Van Heel knows there are things she would have done differently, from big picture decisions about diagnosis and treatment down to small choices of words.

“I’d try telling him that things can always be worse, but that was the wrong thing to say,” she says. “To him, his problems were as bad as everyone else’s.”

Nor is she sure how she could counsel a parent enduring with their child what she endured with Jack.

But she does know, for example, that parents of children with mental illness will have to be “cheerleaders” for their children, because they will need advocates.

“You’re going to have to defend them and there’s going to be crappy people you have to deal with,” she says.

She wishes there had been some sort of group counseling for kids in Jack’s situation, if for nothing else than to assure them that they are not alone. She wishes the education system had a better understanding of and approach to mental illness, one that does not leave people like Jack feeling like an “outcast.”

There were some providers who truly cared about Jack and sincerely wanted to help him, but they were ultimately unable to do so. While Van Heel is grateful to those who tried, she also acknowledges that finding the best providers may mean going far from Montana.

Toward the end of his life, as he approached his 18th birthday, Van Heel knew Jack’s situation was worsening and that there was little she could do to help him. As he abused pills and alcohol, she considered getting him into short-term inpatient treatment, but she also knew that it would take time to find him a bed in a facility. If he turned 18 before that could happen, the rules of the game would change. Jack would be an adult and could make his own decisions.

“That was the rock and a hard place I was in the last month of his life. I knew we were drowning but he was done with the help … Yes I could get him a 72-hour commitment, but it would result in him walking out of there in 72 hours no better off,” she says.

On Friday, Aug. 26, Jack ended his life. Van Heel found his body at a neighbor’s house.

She chose to celebrate Jack’s life on Sept. 12, on what would have been his 18th birthday. About 100 people attended, from “all walks of life,” she says.

Those attendees included everyone from the local clergy he had discussed religion with, to officials from Montana’s Office of Public Instruction who had helped Jack with his special education plan; from people he had worked with at his jobs over the years to the school cook who often ate lunch with him in elementary school because he usually sat alone; from his girlfriend, whom he met online but had never met in person, to the small cadre of friends who had stuck by him.

“Jack would have been amazed at the people. He never would have guessed that it would have come to this,” she says.

The people at Jack’s celebration all shared one thing in common. They had all taken the time to get to know Jack. They had discovered that his outward appearance may have seemed intimidating, but on the inside, he was just a young man trying to find answers and hoping to be respected.

It is because of Jack’s desire for respect that Van Heel wants to talk about him and his death.

“I want people’s perspective of people who are different and have mental illnesses to hopefully change so it’s not such a horrible label to have, and make you somebody society shies away from because they are scared of you and figure you’re a freak and don’t fit,” she says.

She worries that even within the mental health care system, patients are treated more like “a project or less than a normal person. It’s not maybe the world around you that needs to do something different, but you are the problem. You need to change, you need to medicate, you need, you need, you need. That was Jack’s struggle. No matter what he tried to change about himself and what he tried to do different, the people around him remained the same.”

What Jack craved was to be respected as an individual. Van Heel hopes people take that to heart.

“It costs nothing to bite your tongue, smile, and be decent. It can cost someone so much with one nasty remark,” she says.

To that end, his life and death have had ripple effects. His younger siblings, Xander and Melanie, have taken to heart the importance of kindness. Melanie tries to be kind to everyone and speaks out against bullying; Xander received a citizenship award at school for looking out for his classmates, Van Heel says.

Skiera went through a period of questioning whether she had missed warning signs. She and other classmates spearheaded an effort for Jack and another classmate who died to be remembered at their high school graduation ceremony in May 2017.

Now, she encourages compassion. “It’s ok… to be scared as a friend of a person you are concerned about,” she says. “But you stepping out and lending a hand could save someone’s life.”

Since Jack’s death, Van Heel has counted each Friday as it passes. She thought she would stop her count at 52 – the one-year mark – but it has continued. Each Friday morning, she writes Jack a note to tell him what has happened in the last seven days.

“Not that he doesn’t know what’s going on, but that’s what I do,” she says.

A note about Montana Gap series

Kate Schimel Deputy editor-digital High Country News

In late 2017, Montana legislators voted to substantially cut funding for mental health care, in response to a budget shortfall. In the wake of the budget cuts, a group of Montana newsrooms, in collaboration with High Country News and the Solutions Journalism Network, explored how communities are preventing the state’s mental health crisis from worsening. What we found was a rise in informal treatment options: Rather than replacing the mental health workers whose jobs disappeared, communities are building on-the-ground care networks. The effects of that shift on Montana’s mental health system are still emerging. This series is just the beginning of a statewide conversation about what a successful system could look like.

.jpg)