Chasing the curve: As budgets churn, can Montana get its mentally ill care before they hit crisis?

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

2 of 3 free articles.

Sarah sat in her Livingston home with the front door locked and her eyes closed, picturing the path to Gallatin Mental Health Center in Bozeman for day treatment. It’s 26 miles, across a pass, with strangers at the end of the trip — too far, for someone who struggled to imagine walking around the block.

Her dark hair faded with grey lines, Sarah has dissociative disorder. That means she lives with episodes that steal reality, creating people who aren’t there and stalling her sense of time.

“I’m suicidal, anxious, I panic,” she said, gripping the fabric of her dress. “When I start thinking about things, my mind goes where it shouldn’t.”

Before this spring, Sarah received treatment at Livingston Mental Health Center — until she and 100-plus clients got a letter announcing the center was closing following a round of state budget cuts. Instead of making the trip to Bozeman to get help from the center there, she stayed home alone. Wanting to feel “normal,” she stopped taking her medication.

“I’m scared of people and different places,” said Sarah, who wanted her true name kept private as she continues treatment. “Bozeman was never an option.”

Instead, her mind draped the world outside her home where she lives alone with characters of terror. Eventually, she dialed a familiar number — the national suicide hotline. Then she waited for police to take her to the emergency room.

For Sarah — one of an estimated 42,600 Montanans who have a serious mental illness — the state’s network of mental health services is a lifeline to what’s outside her home when her thoughts begin to race.

But as budget cuts ripple through state health care programs — the latest in a series of up and down swings — many worry about where the system is heading and what its fate means for people like Sarah across the state.

Montana has historically plugged more money into mental health on a per capita basis than most of its neighbors. It’s also tended to rank below many of the states it outspends when it comes to measures like suicide rates or residents’ ability to get the services they need.

There’s a broad sense across state leaders, providers and clients that something needs to change. And people across the mental health system say it makes sense to invest in services that help Montanans before they land in emergency rooms or jails — something state officials say they’ve only had money for recently, as a result of the state’s 2016 Medicaid expansion.

“We need to be focused on prevention and early intervention wherever we can,” said Zoe Barnard, the top mental health official with the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services.

“It needs to be generally acknowledged that recovery from mental illness and substance use disorder is possible, and that with the right support people can live happy and productive lives,” she said.

What’s less clear: How exactly Montana can get there.

The back story

Over the past year, most of the news about mental health in Montana has been focused on a wave of budget cuts like the mental health center closure in Livingston — the consequence of legislators and state officials trying to resolve a major revenue shortfall by squeezing health and human service programs.

However, Montana has historically been something of a big spender on mental health, children’s services in particular.

The state spent $249 million on state mental health services during the 2014-15 fiscal year, according to data compiled by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. That’s equivalent to $241 per resident, the seventh-most of any state in the nation and well above neighbor states like Wyoming, Idaho and the Dakotas. North Dakota’s 2014-15 spending figure, for example, was $94 per capita.

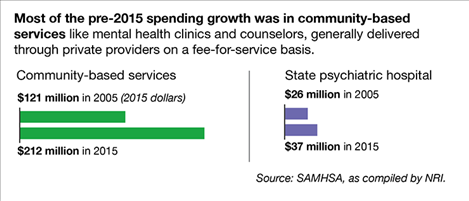

Montana’s primary response to mental illness was once housing patients at the state hospital in Warm Springs. The deinstitutionalization movement of the 60s and 70s saw the state shift toward providing all but the most severely ill patients services in their home communities. In practice today, that means most of Montana’s publicly supported mental health care is delivered through a fee-for-service model, where private community providers offer crisis intervention or counseling and then bill the state health department.

In turn, most of the mental health money doled out by the state comes from the federally funded Medicaid program, which exists to provide health care services to low-income Americans. Missoula-based nonprofit Western Montana Mental Health, for example, funded $27 million of its $40 million budget through Medicaid in 2016, according to its annual audit report.

Montana’s mental health budget also grew substantially over the decade before 2015, the most recent year where the federal government has published financial data. The number of Montanans served by it also increased, reaching 42,000 people in 2015. That puts Montana’s usage rate for state mental health services at more than twice the national figure — and 3.5 times the national rate for kids and teens.

Even so, advocacy group Mental Health America has consistently scored Montana poorly for mental health care access — a measurement it bases on insurance coverage and how many people with mental disorders go untreated. The group’s most recent scoring, using data collected before Montana’s 2016 Medicaid expansion, ranks the state 29th in the nation for access. North Dakota, despite spending less than half as much per resident on its mental health system, comes in at 15th.

Federal data also points to gaps in the state’s mental health system. Just over half of adult mental health clients surveyed about their treatment in Montana in 2015 said it helped them do better in their day-to-day lives, compared to three-quarters of clients nationally.

As it has for more than 40 years, the state’s suicide rate remains among the highest in the nation. Between January 2014 and March 2016 alone, Montana lost 555 people to suicide, according to a report by a state task force — 84 of them younger than 25.

A budget roller coaster

In the past two years, Montana’s healthcare system has been rocked by a pair of sweeping changes — first state-level Medicaid expansion in 2016 and then this year’s budget cuts.

As part of the 2010 Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare, states were given the option of expanding their Medicaid programs, accepting more federal money to provide more residents with coverage. Despite vocal opposition from fiscal conservatives, Montana lawmakers voted in 2015 to adopt expansion through the Montana HELP Act.

Health advocates and state officials point to the expansion — facing a renewal fight in the next year — as a seminal moment for the state’s healthcare system, including programs aimed at treating addiction and mental illness. Officials say the federal dollars that expansion injects into the system make it possible for thousands of lower-income Montanans to afford services like counseling or treatment for substance use disorder.

Crucially, Barnard said, the expansion also gave the state mental health division breathing room to direct more money to preventative programs. She said prevention had been neglected in the past in favor of must-fund crisis services like providing severely mentally ill people with medication.

For example, the Medicaid expansion funneled $7.7 million into chemical dependency programs for people with drug or alcohol addictions in 2017, funding care for almost 3,000 patients, according to figures provided by DPHHS. It also provided $3.5 million to help 5,300 Montanans receive counseling — something Barnard said makes it easier for people to get help for mental illness before their condition gets so severe they end up in an emergency room.

“That should pay dividends for the state into the future, not on a biennial kind of schedule but on a generational kind of scale,” Barnard said.

Over the last year, health advocates efforts’ to tout the benefits of expansion ran headlong into another set of headlines: providers and patients protesting what they called crippling budget cuts to community care. Those reductions came as tax collections fell below projections and an expensive fire season drew down the state’s reserves.

Implementing cuts ordered by the Legislature, the health officials lowered the reimbursement rates providers get through Medicaid, cutting compensation for most services provided through mental health centers like Western Montana Mental Health by 3 percent. The hourly rate for case management work, which legislators singled out, was reduced from $72.88 to $32.76.

Barnard said the state health department can’t estimate how much those cuts will reduce state mental health spending because it’s tricky to predict how lowering rates will shift the services independent providers bill for. In any case, newer revenue projections raise the prospect that the state may actually bring in the money to reverse some of its cuts.

What is clear, though, is that the cuts have rocked the Medicaid-dependent system. Western Montana Mental Health, for example, closed offices in Libby and Dillon and also shut down its Livingston Mental Health Center, where Sarah was getting care, at the end of April. The system’s Bozeman branch Gallatin Mental Health worked with local organizations to transfer patients losing services.

“At the end of the day, we cannot continue at the rates provided to us and make it work,” Gallatin Mental Health Executive Director Michael Foust said as he announced Western Montana’s Livingston location would close.

‘What is the strategy?’

In the wake of the cuts, health department Director Sheila Hogan traveled the state in February holding listening sessions with mental health workers and advocates. When her tour stopped in Gallatin County, Foust asked her to explain the logic behind the way cuts were done.

“What is the strategy going forward and where can we get our hands on that so we can get behind it and partner with you?” he asked.

Foust said a plan has the potential to create a culture that connects scattered Montana towns and people to what’s coming from the capitol — something that he said is missing today.

Even with the moment’s budget crisis, the state is obligated to plan for prevention. That’s according to the national President of Mental Health America Paul Gionfriddo.

“People can point all they want to the demands placed on state budgets, but you still make choices of what you’re going to fund,” Gionfriddo said. “We should not be letting so many people get to crisis. If they don’t do prevention, the state will continue to overspend relative to the services it gets.”

Gionfriddo said states that Mental Health America holds up as examples passed early versions of Medicaid expansions, created options for care for people outside of “poor houses,” jails and institutions and also have a history of mental health screenings woven into primary doctor appointments and school checkups.

A number of Montana’s neighbors, including punch-above-its-spending North Dakota, have invested in comprehensive studies of their mental health systems, projects geared toward identifying what’s working and what’s not. Idaho, for example — which spent almost four decades in litigation over the conditions in its kids’ mental health system — released a major assessment of its efforts this year, recommending more investment in preventative care.

In North Dakota, a 249-page “Behavioral Health System Study” released in April discusses what an optimal state mental health system would look like while cataloguing the strengths and weakness of the status quo. For example, the study discusses how limited options for mental health treatment sometimes mean North Dakotans can’t get care unless they’re convicted of a crime that gives them access to services in prison. It also points out that a number of entities in North Dakota are working on screening initiatives to identify and help people in the early stages of mental illness — and suggests the state do more to encourage those efforts.

“(S)takeholders emphasized a need for a system that incentivizes wellness rather than focusing only on sickness,” the study authors wrote.

Montana officials like Barnard talk about similar ideas, but say they haven’t had the time to articulate that big-picture thinking in a formal document and add they want to help individual communities do local planning in any case. They also point to the unclear future of the Medicaid expansion, saying a legislative refusal to renew the program would devastate their ability to focus on prevention with any degree of strategy, forcing them back to the days of spending limited funding on crisis care.

“Trying to improve the system is a continual goal. It’s not something that we ever reach the end point of,” Barnard said. “The department is committed to continuing to look at the services that we provide for all Medicaid members.”

What comes next

Nationally, the way people expect states and providers to deliver mental health treatment is changing.

“People are looking for help that goes out beyond the doors of a center or mental health hub, out into a community,” Gionfriddo said. “The system is going to transform and that’s never easy.”

When Sarah landed in the emergency room, a social worker and former Livingston center employee showed up at her bedside. The new role is part of the hospital’s growing integrated behavioral health system, which weaves mental health professionals and support into primary care. Sarah learned another adult treatment program, L’esprit, opened in Livingston in her months of isolation.

“I was so scared about what would happen before I found this place,” Sarah said on a recent afternoon, sitting alongside people she calls her family at L’esprit. “This feels more steady, like it won’t go away, which puts my mind at ease.”

L’esprit founder Chantelle Plauché said she’s able to combine graduate interns and full-time staff to build on the services the center already offered children, even with the cuts. For what they can’t cover, the building is a few doors down from Community Health Partners, one of several local groups they’re working with more.

“Everybody got knocked to their knees when the budget cuts came, but you had to approach it like, ‘The work is still very important — how can we still provide this work and move forward?’” she said.

L’esprit employees say the small community is the exception. Many Montana towns that lost services weren’t able to fill in the gaps. Others didn’t have services to lose in the first place. Plauché said what’s happening in Livingston takes time, community investment and, ideally, continued buy-in in funding and time from the state.

“We all have to look at being more efficient,” she said.