Tribal Water department monitors water, confident in science

Megan Strickland

Irrigation headworks at the Pablo Feeder Canal are monitored by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and could be impacted by a proposed water compact pending before the legislature.

Megan Strickland

Each water monitoring site has an extensive handwritten file that contains troves of metadata.

Megan Strickland

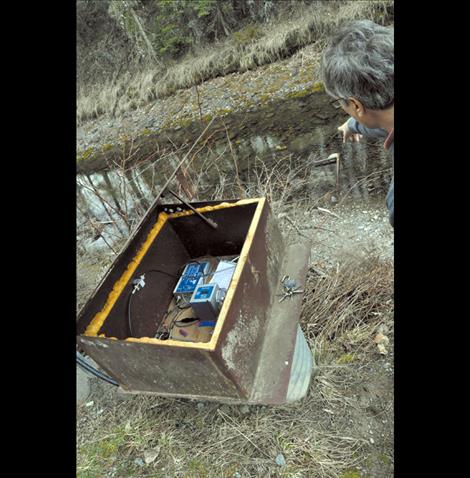

Tribal hydrologist Seth Makepeace stands near part of a water measurement system in Pablo

Megan Strickland

Megan Strickland

Megan Strickland

Megan Strickland

Megan Strickland

Megan Strickland

Issue Date: 4/8/2015

Last Updated: 4/8/2015 12:57:22 AM |

By

Megan Strickland

Keep Reading!

You’ve reached the limit of 3 free articles - but don’t let that stop you.