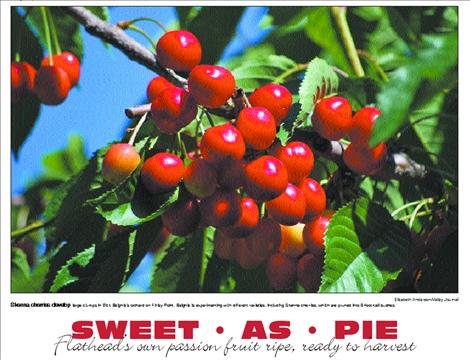

Flathead’s own passion fruit ripe, ready to harvest

Elizabeth Anderson

Skenna cherries develop large clumps in Dick Beighle’s orchard on Finley Point. Beighle is experimenting with different varieties, including Skenna cherries, which are pruned into 8-foot-tall bushes.

Elizabeth Anderson

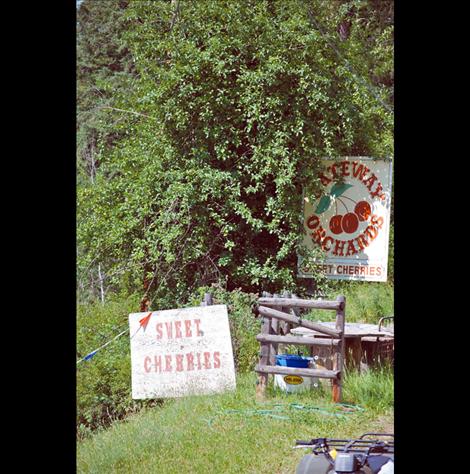

Barbara Kaye sells her cherry crop at Gateway Orchards on Hwy. 35, where her 80-year-old trees are still producing.

Elizabeth Anderson

Barbara Kaye sells her cherry crop at Gateway Orchards on Hwy. 35, where her 80-year-old trees are still producing.

Elizabeth Anderson

Barbara Kaye sells her cherry crop at Gateway Orchards on Hwy. 35, where her 80-year-old trees are still producing.

Elizabeth Anderson

Barbara Kaye sells her cherry crop at Gateway Orchards on Hwy. 35, where her 80-year-old trees are still producing.

Issue Date: 7/23/2014

Last Updated: 7/23/2014 1:00:16 AM |

By

Elizabeth Anderson

Keep Reading!

You’ve reached the limit of 3 free articles - but don’t let that stop you.