Indigenous researchers gather at Salish Kootenai College

Nicole Tavenner

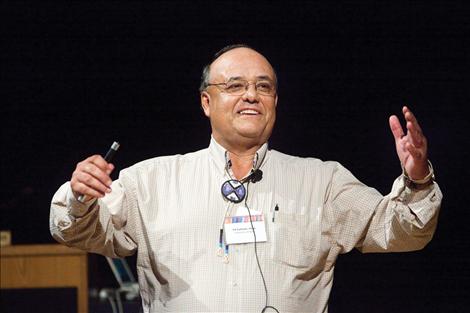

Dr. Shawn Wilson opened the first-ever American Indigenous Research Association conference, held Friday and Saturday at Salish Kootenai College in Pablo.

Nicole Tavenner

Participants packed the Johnny Arlee/Victor Charlo Theater at Salish Kootenai College.

Nicole Tavenner

Former NASA astronaut John Herrington, enrolled member of the Chickasaw Nation, talked about his mission in space.

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Author, presenter and conference coordinator Lori Lambert

Nicole Tavenner

Dr. Ed Galindo of the University of Idaho

Nicole Tavenner

Dr. Shawn Wilson opened the first-ever American Indigenous Research Association conference, held Friday and Saturday at Salish Kootenai College in Pablo.

Nicole Tavenner

Former NASA astronaut John Herrington, enrolled member of the Chickasaw Nation, talked about his mission in space

Nicole Tavenner

Dr. Shawn Wilson opened the first-ever American Indigenous Research Association conference, held Friday and Saturday at Salish Kootenai College in Pablo.

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

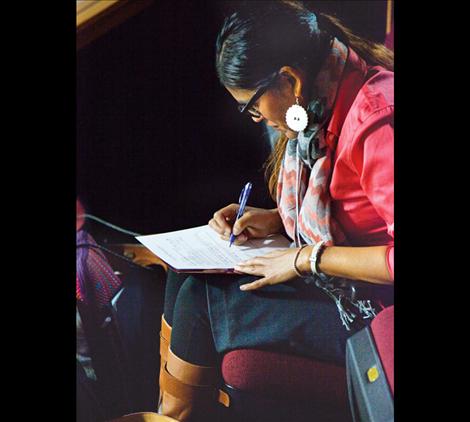

A participant takes notes at the American Indigenous Research Association conference Friday at Salish Kootenai College.

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Badges and beautiful beadwork were common sights at the conference.

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Corinna Littlewolf

Nicole Tavenner

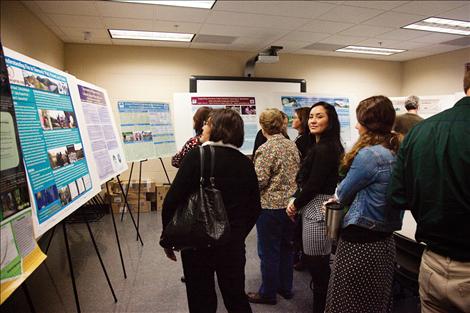

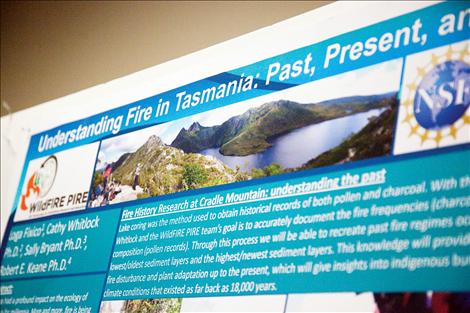

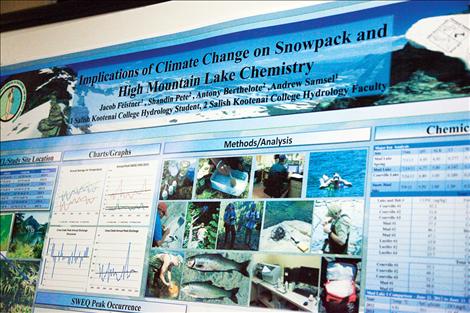

Research posters created by SKC students were on display in Allen Hibbard's classroom.

Berl Tiskus

Fiona Cram

Nicole Tavenner

Research posters created by SKC students were on display in Allen Hibbard's classroom.

Berl Tiskus

Sharon Austin

Nicole Tavenner

Research posters created by SKC students were on display in Allen Hibbard's classroom.

Nicole Tavenner

Salish Kootenai College

Nicole Tavenner

University of Montana grad student Matthew Croxton views posters created by SKC students were on display in Allen Hibbard's classroom.

Nicole Tavenner

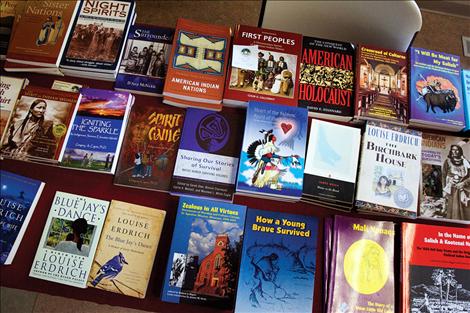

SKC bookstore had a selection of books available in the Camas room in the Joe McDonald Health and Fitness facility.

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Participants register for the conference.

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

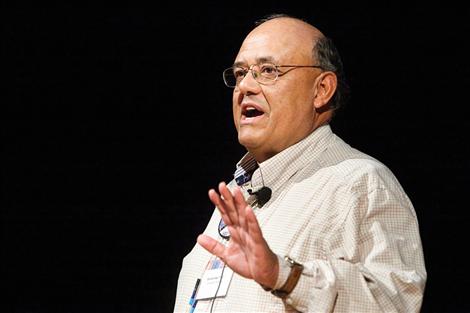

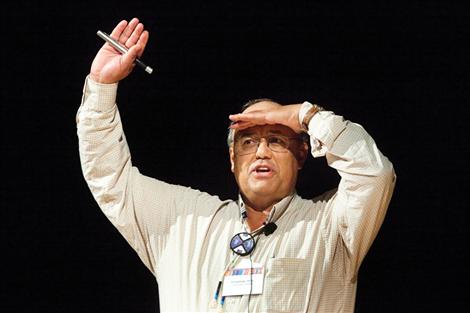

Dr. Ed Galindo of the University of Idaho

Nicole Tavenner

Dr. Ed Galindo of the University of Idaho

Nicole Tavenner

Dr. Ed Galindo of the University of Idaho

Nicole Tavenner

Dr. Ed Galindo of the University of Idaho

Issue Date: 10/16/2013

Last Updated: 10/16/2013 7:48:03 AM |

By

Berl Tiskus

Keep Reading!

You’ve reached the limit of 3 free articles - but don’t let that stop you.