MSU work set to launch June 26 on NASA mission

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

News from

Montana State University

BOZEMAN — Montana State University faculty and students who designed and tested optics for a NASA solar mission are hoping to watch their work head into space tonight.

The Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) is scheduled to launch at 8:27 p.m. Mountain time from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.Tthe public has been invited to watch with the scientists from 7:30 to 9:30 p.m. in the planetarium at MSU’s Museum of the Rockies. NASA will also offer the public several opportunities to follow the launch on NASA’s home page at http//www.nasa.gov.

“It’s very exciting to see the work of so many people come together,” said Charles Kankelborg, leader of the IRIS team at MSU. “A rocket launch like this is such a focal point and such a milestone.

“You know that things usually go just fine, but it’s always very stressful, and you always worry,” Kankelborg added. “It’s always very exciting. The only satisfying way to enjoy it is to hold a party and invite a lot of people.”

MSU became involved with IRIS in 2007 after Kankelborg attended a solar physics meeting in Honolulu and long-time colleagues at Lockheed Martin approached him about collaborating. Kankelborg had come to MSU in 1996 from Stanford University where he earned his doctorate in physics.

In the past six years, more than a dozen people at MSU have helped design and test optics that are part of the IRIS mission to answer some of the biggest questions about the sun, Kankelborg said.

One of the biggest mysteries about the sun is why the corona is millions of degrees Celsius when a layer closer to the sun is much cooler, Kankelborg said. That layer, the photosphere, averages 6,000 degrees Celsius.

IRIS will focus on the layer between the photosphere and corona – the chromosphere. Expected to give the most detailed look ever of the sun’s lower atmosphere or interface region,

IRIS will observe how solar material moves, gathers energy and heats up as it travels through this largely unexplored region of the solar atmosphere. The interface region, located between the sun’s visible surface and upper atmosphere, is where most of the sun’s ultraviolet emission is generated. These emissions affect the Earth’s climate and can interfere with satellite communications and the transmission of power.

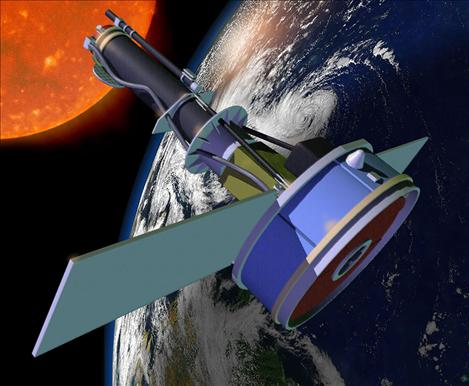

IRIS will carry an eight-inch ultraviolet telescope, a spectrograph that contains MSU optics, and a “bus” carrying transmitters and batteries. It will fly 390 to 420 miles above Earth and pass over the poles every 90 minutes. The telescope is tentatively scheduled to open for the first time on July 17. The occasion, called “First Light,” is the next big thing after the launch, Kankelborg said.

Once the telescope opens, it will transmit ultraviolet light to the spectrograph. The spectrograph will then split invisible light into wavelengths like a prism splits visible light. This allows scientists to identify physical processes and measure such things as solar temperatures, velocity and composition. At the same time, IRIS will take high-resolution photos of the sun. Scientists will then match the photos and images and analyze the results.

The satellite is the first mission designed to use an ultraviolet telescope to obtain high-resolution images and spectra every few seconds and provide observations of areas as small as 150 miles across the sun.

IRIS is designed to operate for two years, but if it’s like TRACE, it will operate much longer, Kankelborg said. TRACE was launched in 1998 and retired in 2010. It was designed to operate for eight months.

IRIS and TRACE are both part of NASA’s Small Explorer (SMEX) Mission. The goal of the program is to provide frequent flight opportunities for world-class scientific investigations from space using innovative and efficient management approaches.

IRIS was about a $100 million mission. By comparison, interplanetary missions can cost more than $1 billion, Kankelborg said.

He noted that there are cheaper interplanetary missions, such as the upcoming Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN). That mission is projected to cost half a billion dollars.