Answering the call

Dispatchers conquer job stress to carry out duties

Nicole Tavenner

Dispatchers Shelly Wheeler-Burland, left, Devin Wegener and Keith Deetz work a shift in the Lake County Dispatch office.

Nicole Tavenner

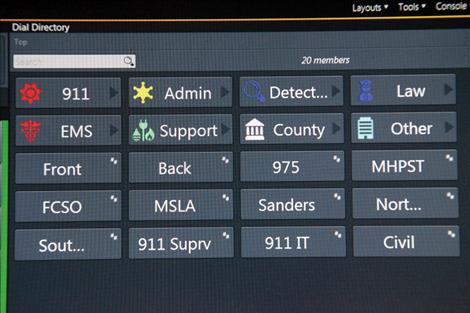

Shelly Wheeler-Burland sits at her dispatch desk surrounded by computer screens.

Nicole Tavenner

A Lake County dispatcher points out county lines and areas covered by dispatch.

Nicole Tavenner

An award won by dispatcher Staycha Hansen stands in a place of honor in the Lake County dispatch center.

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Berl Tiskus

Nicole Tavenner

Nicole Tavenner

Issue Date: 10/15/2014

Last Updated: 10/15/2014 10:12:03 AM |

By

Berl Tiskus

Keep Reading!

You’ve reached the limit of 3 free articles - but don’t let that stop you.