Home on the Range

Karen Peterson photo

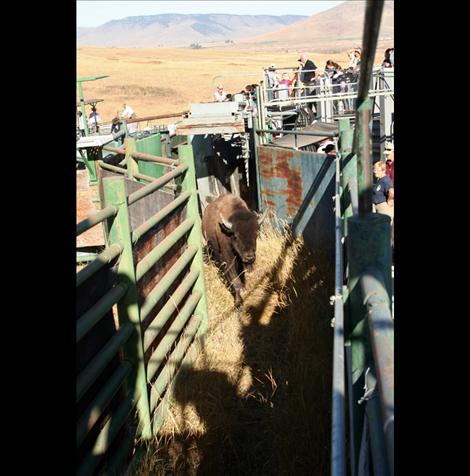

Schoolchildren gather to watch the annual National Bison Range roundup.

Karen Peterson photo

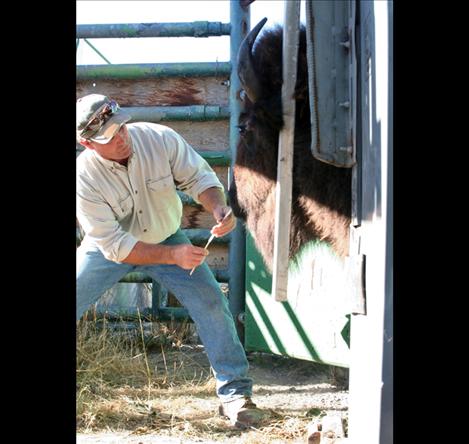

Range staff work on a bison calf in the chute.

Karen Peterson photo

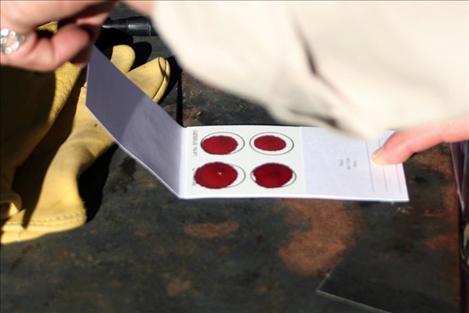

Bison Range staffers take a blood sample to check an animal for disease.

Karen Peterson photo

Visiting students check out bison bones.

Karen Peterson photo

Students and teachers watch as National Bison Range workers sort and test bison.

Karen Peterson photo

Karen Peterson photo

Karen Peterson photo

Karen Peterson photo

Karen Peterson photo

Issue Date: 10/15/2014

Last Updated: 10/14/2014 11:11:47 PM |

Karen Peterson for the Valley Journal

Keep Reading!

You’ve reached the limit of 3 free articles - but don’t let that stop you.